CPH:DOX 2015

With cutting edge programming, CPH:DOX pushes the boundaries of nonfiction film and curates brilliantly imaginative programmes.

Here are 8 Great films - and an exhibition - that stood out this year.

EMBODIED

In collaboration with CPH DOX and Nikolaj Kunsthal, Jacqui Davies curated a brilliant show at the towering former church. Embodied explores the conjunction between documentary and performance and seeks “to go beyond the question of authenticity that is initially raised by this intersection.”

Among the artists are Martha Rosler, ChimPom, Jerome Bel and the psychogeographical Nyau Cinema of Samson Kambalu. In Mourning Class: Nollywood, Zina Saro-Wiwa explores the performative aspect of grieving through the tropes of Nollywood cinema. Fragments of a mourning woman’s face appear across an installation of old televisions. In Teem, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s boyfriend sleeps in a three video installation; “a silent unconscious performance”. Shot on 16mm, Tacita Dean’s Event For A Stage is a fluid exploration of the layers of performance in theatre and film, and the veils of safety created for the audience.

Katarzyna Badach & Alfredo Ramos Fernández’s piece, Surfing Buena Vista, reveals how their subjects escape their reality by the extremely dangerous act of urban surfing; hanging off the back of vehicles, they speed through Havana’s torrential rain. A huge suspended screen on the ground floor exhibited Yael Bartana’s Pardes, in which her close friend Michael undergoes the Ayahuasca ritual with a Brazilian shaman.

Coco Fusco’s film Operation Atropos is a shocking insight into the prisoner of war interrogation experience. A group of women take on the role of the POWs and undergo the violent methods of mental and physical torture by male interrogators. Watching these men lose themselves in their bullying roles is hypnotic, jaw-dropping and raises an array of questions about identity and boundaries between acting and being.

Richard Billingham’s film Ray observes Ray’s solitary existence at the top of a block of council flats, quenching his alcoholic needs. His friend and ex-wife vie for control over his money and well-being. The camera drifts around the flat, with extreme close-ups expressing the claustrophobia yet capturing stunning shades of light. He sings along to a record, and in that vulnerable moment of performance is a unique window into his truth.

The final piece by Louis Henderson, Lies More Real Than Reality was performed in a separate event that explored the concepts within the exhibition with greater depth. Henderson’s performance tells the story of a scam email that developed into frequent correspondence with the scammer. The film (perfectly-timed with his narration) depicts the subsequent online journey, while the narrative that unfolds delves into the nature of ethnographic research and truth in performance.

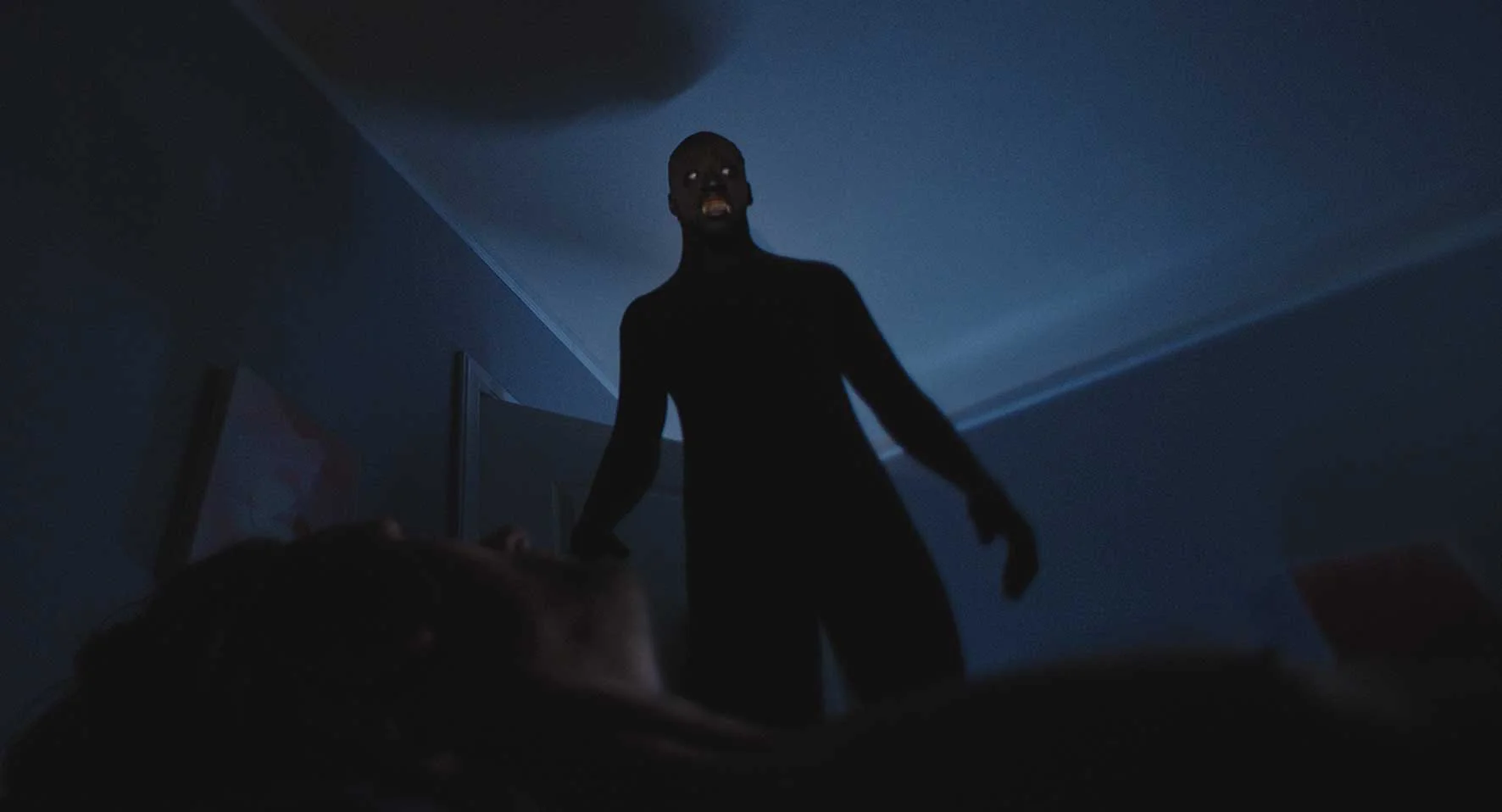

THE NIGHTMARE

After the obsessive’s galore that was Room 237, Ascher shifts to the kind of horror that crouches in the darkness and strikes its victims at their most vulnerable. Sleep paralysis has been a menace to the slumbering mind for centuries, with Henry Fuseli’s iconic 18th century painting The Nightmare, depicting the terrifying unconscious state. Eight people share the relentless torment that seeps into their sleep night after night; the electric surge through the brain before the inevitable descent and recurring shadowy visitors. The reenactments of these experiences build up the sense of terror with slick cinematic aesthetics and powerful sound design. Loosely divided into chapters, the film explores the question of supernatural forces, avoidance tactics and how nightmares and horror movies feed into one another. As the subjects relive their stories, the film animates the imagination, materialising the fear and transporting the viewer into the breathless grip of panic. To see that obscure feeling of fear – and visions that can sound so ridiculous in the light of day –portrayed with such precision, dynamically fleshes out the elusive forces of nightmares.

LOST & BEAUTIFUL

Italian folklore and idiosyncratic pastoral fantasy merge to tell the story of one man’s devotion, from a bull’s eye. The moving target is Sarchiapone, a buffalo calf rejected by his mother who is compassionately adopted by the shepherd, Tommaso Cestrone. Cestrone takes the calf to the deserted Cartidello palace he voluntarily tends to, beautiful royal grounds of deteriorating grandeur. Sarchiapone philosophises on life – and that to survive, one must be born with good luck or a great name. The classical character, Pulcinella, appears in his black beaked mask, and is woven into the fantastical narrative. Filmed on 16mm, the cinematography glistens with soft subterranean shades and magic hour colours that recall Malick’s Days of Heaven. The story poetically stirs political notions with psychogeographical wandering; the economic breakdown in Italy, a shepherd who died looking after the remnants of a bygone era, a country falling apart and a hunted buffalo’s refrain.

HARLAN COUNTY (1976)

One of Naomi Klein’s curatorial selections, it was refreshing to see a credit roll with so many women as the major figures in the film’s production. Screened on 35mm, Barbara Kopple’s portrait of the mining community’s battle against the exploitative big corporation Duke Power begins with the words that encapsulate the callous attitudes of the mine owners: “You can always hire another man, you have to buy another mule.” Kopple gets close to her subjects, and right into the front line of action. The women of Harlan County unite as an indomitable force throughout the strike, laying before cars and devising new strategies. Lois Scott emerges as a fearless warrior in the picket lines, while men are struck down with Black Lung and killed in explosions. The leader of the ‘scabs’ threatens the strikers with his gun and the family of a union representative is murdered, a crime that has obvious connection to the dispute. The rusty colours of the land dust the film in a terracotta hue, while miners’ folk songs soundtrack the film, grounding the events in homegrown, haunting, and beautiful cries of protest.

FRAGMENT 53

Opening with a clip of the capture and torture of Samuel Doe, the former leader of Liberia in 1990, Fragment 53 tumbles the audience into volatile territory from the get-go and sets the tone for escalating dread. The threat of witnessing the unbearable hovers in the peripheries of the unfolding narrative. The film journeys through the experiences of seven warriors of the Liberian civil wars. In a set of beautifully shot interviews, the former warlords pose for the camera and share their stories. The camera gets close. With the chilling frankness displayed in The Act of Killing, the men discuss the cannibalism and butchering they performed to maneuver their way through war. They explain their motives and reasoning; the need to go to such extremes to scare the opposition, the machismo, the roles they played that gave them their battle names. Through the masks and spirituality they incorporated to protect themselves, the bottom line is expressed by Carl Darlington, the only one to confess that he didn’t feel normal after committing a brutal massacre; “nothing can scare you after war.” The tales of extreme brutality are grotesque, yet it is fascinating to hear the stories people tell, and characters they create, to justify their behavior and reconcile themselves with the horror.

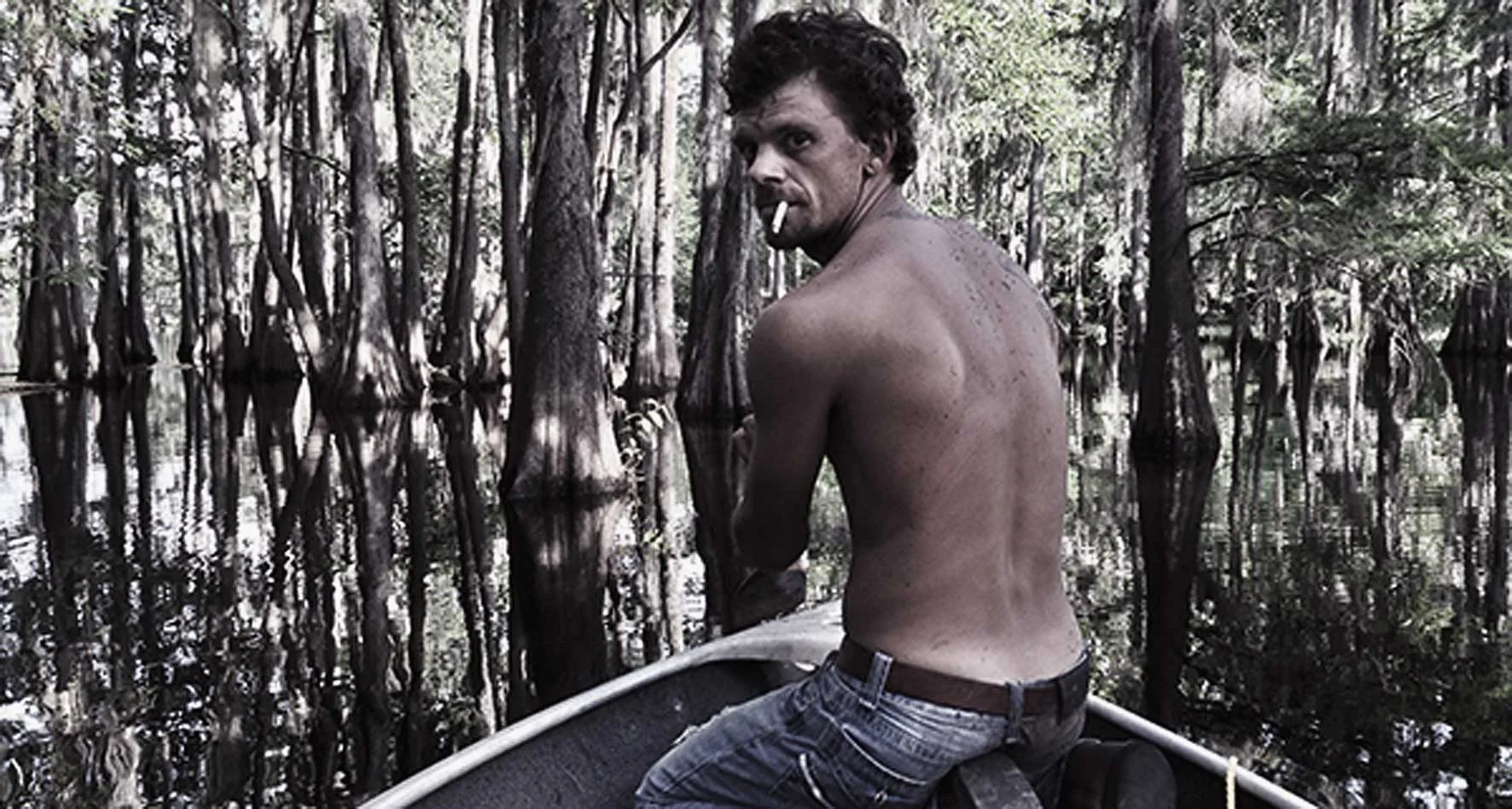

THE OTHER SIDE

Roberto Minervini returned to CPH DOX with his fourth feature film, an intimate, often shocking portrait of the metamphetamine problem in the USA, racism, and the sense of abandonment that leads people to desperate measures. Mark deals drugs and is gripped with imminent loss. His relationship with fellow addict Lisa is passionate and turbulent. A group of old men discuss politics; smashed and desperate they yearn for a leader who cares about them. Men stalk the woods in a faux-military training camp, hunting for the sense of belonging that camaraderie and its masculine posturing offers. Minervini uses real characters, who bring their personal stories into the film, and with his cinematographer Diego Romero, infuses reality with the fluidity of fiction. Minervini lingers on the craved moments of intimacy, sharing the raw emotions felt within the troubled community, and ultimately the violence and destruction spawned by desertion.

FIELD NIGGAS

Khalik Allah’s debut feature film is an observational engagement with the homeless people and addicts of 125th Street, Harlem. With a provocative title that stems from the words of Malcolm X, Field Niggas shows lives under relentless pressure from the police, regurgitated through a prison system that generates profit for corporations. Allah’s photography is beautiful and hypnotic; rich, lurid colours from the neon street signs illuminate the characters as the camera rocks in gentle slow motion. Threads of a prison gang song weave into the disconnected audio and surveillance footage of the murder of Eric Garner emphasises the constant threat faced by African-Americans from racist law enforcement. The audio is staggered with the visual, encouraging a more imaginative, sensory engagement with the subjects and experiences. Arguing, flirting, getting high on K2 – a potpourris laced with a chemical that generates a high similar to weed – the film is reminiscent of William Eggleston’s Stranded in Canton; intimate in its portrait of a community intoxicated as a means to escape reality.

STAND BY FOR TAPE BACK UP

It is human nature to look for patterns. Ross Sutherland begins with the rites of passage that many students go through – syncing up Pink Floyd with Wizard of Oz or Alice in Wonderland and being blown away by the uncanny synchronicity. Could there be meaning beneath the superficial surfaces of our popular culture? Stand By For Tape Back Up is a personal relationship with a VHS tape that stands as the last lifeline between Sutherland and his deceased grandfather. It is an artifact of a time when recording the TV meant you had layers of TV programmes slapped over one another, snippets of previous recordings peeking out, well-worn adverts in between, a collage of analogue. With humour and longing, Sutherland recalls his life, his close relationship with his grandfather and how after watching his grandfather’s tape repeatedly, he began to feel that every single frame directly related to the mystery of his existence. The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, The Crystal Maze, a Natwest advert; all feed in to a spoken-word performance that leaves no fleeting onscreen glance, movement, or shot unturned. Never missing a beat, Sutherland reads between the lines of the random sequences on the video, and as if decoding a message from another frequency, detects the significance in the arbitrary.

THE RUSSIAN WOODPECKER

Shining luminous pyramids, cold war fears and callous politicians pervade the layers of secrets and lies surrounding the Chernobyl disaster. Central to the film’s story is Fedor Alexandrovich, a Ukranian artist evacuated to an orphanage in 1986 as a 4-year-old amid nuclear contamination concerns. With radiation in his bones, he embarks on an impassioned, angry hunt for the truth. Returning to the ghost town of Chernobyl he submerges himself in its haunting ruins. Intense and determined, his eyes flicker to the camera as he boldly interviews key figures of authority in the Soviet dictatorship. 100,000 people were permanently displaced, and civilians unwittingly exposed themselves to radiation drizzle by just leaving their homes. Tensions are mounting in Kiev as the horrendous attack on the Maidan protestors is imminent. Fedor and the cinematographer Artem Ryzhykov, employ a myriad of methods to uncover the truth that links the mysterious Duga tower to the nuclear disaster. The question of how far they can safely go with the film becomes crucial in this oppressive culture where the government threat is palpable.